On March 3, 1966, the film that would become screen legend Lana Turner's (1921-1995) final starring role in a major production — she was just 45 — was released: Madame X.

As well-trod a story in 1966 as A Star Is Born was in 2018, Madame X is, by now, forgotten by popular culture, a dated story that originated in Alexandre Bisson's (1848-1912) 1908 play, one that portrays an imperfect mother as the ultimate martyr who must die in despair for her transgressions.

Not exactly begging for a 2019 remake.

In the original story, the protagonist is a young woman caught having an affair after bearing her husband a son. Shamed for her sin, she is cast out of the home by him and warned from ever trying to see her child again. A lost soul, she sinks into utter ruin, winding up, decades later, the mistress of an unscrupulous man who plans to blackmail her former family. In order to shield her son from shame, she murders her lover and plans to accept the death sentence for it, only to find that her court-appointed lawyer is her grown son! She refuses to give her name, becoming known in the press as "Madame X," and dies never having told her son the truth.

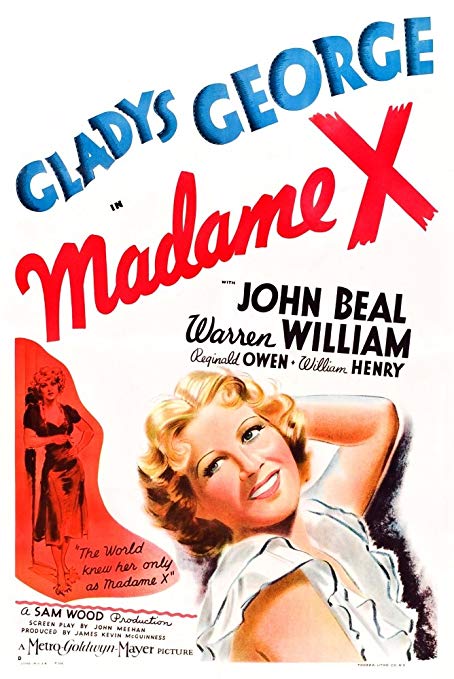

The story was filmed 10 times, starring: Dorothy Donnelly (1880-1928) in 1916; Pauline Frederick (1883-1938) in 1920; Ruth Chatterton (1892-1961) in 1929; Gladys George (1904-1954) in 1937; Mara Russell-Tavernan (1909-1972) in 1948; Gloria Romero (b. 1933) in 1952; Cybele (1888-1978) in 1954; Libertad Lamarque (1908-2000) in 1955; Turner in '66; and Tuesday Weld (b. 1943) in a made-for-TV movie in 1981. It hasn't been touched since.

See Tuesday Weld's Madame X HERE!

Of these, by far the most famous and successfully realized was Turner's, produced by Ross Hunter (1926-1996), who had given her a smash in 1959's Imitation of Life, and directed by the prolific David Lowell Rich (1920-2001).

Hunter announced he would produce the film in May 1962, with Turner attached as its star. Turner, in spite of several late-career successes, was considered somewhat over-the-hill and in need of another hit, but no matter — her star discourse, her real life, played beautifully with the storyline. Just four years earlier, Turner, who had scandalously bedded gangster Johnny Stompanato, had been disgraced when her teenage daughter Cheryl Crane (b. 1943) stabbed the mobster to death. His death resulted in a sensational trial and public shaming that led to her daughter's acquittal after Turner's tearful testimony that Crane had only stabbed the crook in defense of her mother's life.

Turner's unique place in the Hollywood firmament as a femme fatale and mother lioness made her a natural for the melodrama, Hunter sensed.

Jean Holloway (1917-1989) wrote the updated screenplay with Turner in mind, complicating the story deliciously and attempting as much as possible to freshen up the plot.

In the new version, Lana's character, Holly Parker, is a young-ish woman from the wrong side of the tracks who marries an upwardly mobile politico, Clay Anderson (John Forsythe, 1918-2010), much to the chagrin of his uppercrust mother, Estelle (Constance Bennett, 1904-1965). Holly bears Clay a son, Clay Jr., but is reluctantly drawn into an affair with a notorious playboy named Phil Benton (Ricardo Montalban, 1920-2009) when her husband's work keeps him away from her for months on end.

"In our neck of the woods, it's the facade that counts — it covers our corrosion," Benton tells Holly early in their courtship, referring to their Connecticut town as a "breeding ground of the shallow set."

This speaks to Holly, who's overwhelmed by her social duties — and by her need to be reminded she is a flesh-and-blood woman.

Push literally comes to shove when Clay promises Holly they'll finally settle down in D.C. and she visits Benton to break things off. He forces himself on her, leading to an accidental tumble down a flight of stairs that kills him. In a panic, Holly returns home, only to find that her mother-in-law had been having her tailed by a detective. Now, holding all the cards, Estelle tells Holly she's always been an "embarrassment."

"You can't help what you are anymore than you can help what you aren't," Estelle seethes. "You've always been in over your head ... You're still a little shop girl from San Francisco. You should've stayed on the other side of the counter."

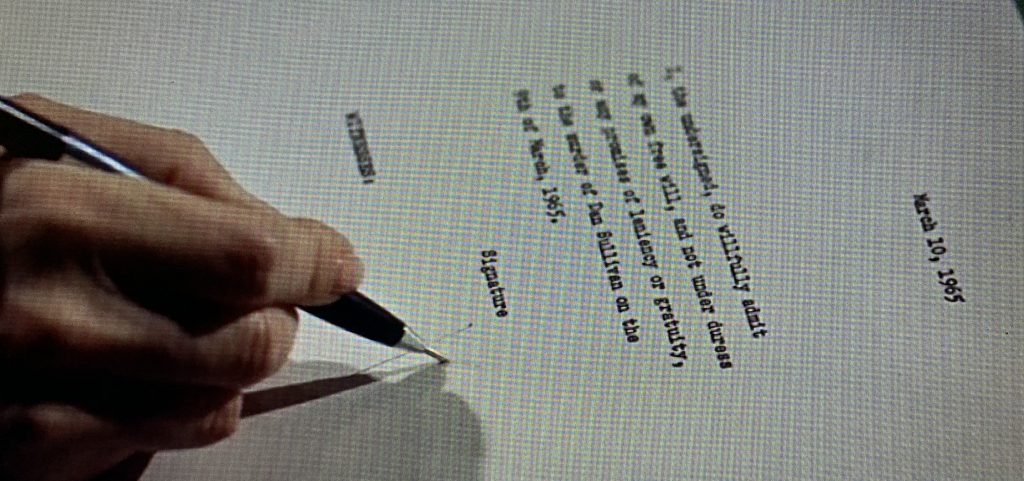

Estelle gives Holly an awful ultimatum — stay and see her family destroyed as she endures a messy trial, or leave forever, faking her own death so her husband and son can live outside the shadow of her adulterous indiscretion. Going against everything in her soul, Holly agrees, disappearing during a cruise to live in Europe on a stipend provided by Estelle.

As soon as she's apart from her family, Holly's mind snaps, and she nearly dies of exposure. Rescued by a handsome musician, Christian (John van Dreelen, 1922-1992), she finds him trying to replace the void in her heart — but she can't allow herself happiness, not after what she's done, so she flees, quicky spiralling into a drunken, sexed-up, globe-trotting stupor from which she will never fully emerge.

Ensconced in what she deems "the cesspool of the world" (sorry, Mexico!), Holly is — decades later — taken advantage of by a two-bit hood played by Burgess Meredith (1907-1997) who finds out her secret thanks to her inebriated ramblings. He tricks her into a trip to New York, where she finds out he plans to use her to blackmail her husband, now on the cusp of becoming his party's nominee for the U.S. presidency. Holly ruins his set-up then shoots him dead — anything to protect her son from shame.

Arrested for murder, Holly refuses to give her name, so the press dubs her "Madame X."

Her approach to her trial is characterized by her desperate plea, "Take my life — the sooner the better. Take it!"

She is assigned a young lawyer to defend her, but doesn't realize that he's actually her beatific son, all grown up (Keir Dullea, b. 1936). Nor does her son recognize Holly, nor does her husband, apparently read the papers, because he doesn't realize his son is defending his supposed-to-be-dead wife and she doesn't realize her lawyer is her son until just before the trial ends. When it all clicks, it's all too much for the absinthe-addicted mother of all mothers, and she winds up with a decision to make on her deathbed — clue her son in, or die with the secret? She chooses the latter, after a dramatic courtroom speech designed to compel her husband to keep quiet, too.

"The moments of love are the only ones that matter," Mama X whispers to her son, proud and relieved that he is doing well and has a girl of his own. "The moments of love illuminate, and are gone. Treasure them."

Madame X dies in anonymity, and the film ends just before the verdict is read.

The film carried high expectations, and some critics had their long daggers out. In advance of its release, Hunter had told The L.A. Times in 1965, "Tearjerkers are more difficult to make than any other type of movie. Critics would seem to categorize them and look down on them; it is word of mouth that is their best press agent. It's all very sad in a way; maybe this is why we're not building great woman stars for audiences today. Audiences need to let their emotions out."

He went on to say that for the first time since The Bad and the Beautiful (1952), Turner was giving "a truly great performance," a backhanded compliment since she had appeared in Peyton Place (1957) and his own film, Imitation of Life, in the interim.

Some critics were impressed with Turner's rich performance. She gives a typical "who me?" turn in the first third of the film, pretending to be a young mommy who has happened her way into furs and jewels, but in spite of the creaky, melodramatic tone, she becomes progressively compelling, sobbing on cue over her character's heart-rending decisions and the loss of her son. Aging 20 years on the screen, Turner allows herself to look dreadful, as dreadful as Holly feels. Every bit of the boozing and carousing shows on Turner's skillfully made-down face, even as her continual transformations — hair! makeup! clothes! — please audiences hungry for glamour.

Variety wrote that the film was "an emotional, sometimes exhausting and occasionally corny picture," but that Turner's performance would be seen by many as her most rewarding portrayal. They were right — she's so good she helps the audience understand why Holly would cheat on her husband, and never loses the character any sympathy as she disagraces herself.

The New York Times was more cynical, branding it a women's picture (gasp!) and stating the film was "the kind of vehicle that went out with the Model T Ford — the saga of a good-hearted woman, forced to abandon her child and husband, who hits the skids and finally ends up as a derelict on trial for murder, defended by a son who doesn't recognize her. The sheer weight of such a teary theme is bound to be affecting to some extent, even played on a banjo."

I disagree. Though it's hard for me to imagine a millennial appreciating such a confoundingly antifeminist creation — a woman destroys another woman who isn't good enough for two men, and the second woman allows her to do it — the film stands up as a period piece (albeit not the period in which it was made) thanks to Turner's gutsy portrayal and the film's confident embrace of light, shadow and lurid gels to paint the story in broad, Greek-tragedy strokes.

Onetime superstar Bennett is a Lucille Bluth-ian delight, and it remains shocking to contemplate the fact that in real life, she dropped dead of a cerebral hemorrhage shortly after filming wrapped. Her old-school, frosty charm gives way magnificently to malignant hatred and determination.

Forsythe has great chemistry with Turner, as does Montalban, who may have been presenting career-high work as the suave lothario who never expects to fall in love, let alone fall to his death. His surprise when Holly turns him down is palpable, as is her disgust at his inability to be an adult and let her walk away.

The only segment that really does not work involves Holly's time with Christian. It seems one self-flagellation too far that she would rather become a destitute drifter than to allow this kind man to care for her, but I suppose it is another illustration of her desire to atone for her, well, desire.

Overall, there are many moments that stretch credulity — chief among them Holly's total disappearance delivered via hair dye — but if you can go with the form, this is an underrated example of it. If only Estelle had died at the end instead of Bennett, because we could really use some justice for Madame X.

Watch for the film to pop up in conversation now that Madonna, 60, has named her new album Madame X. It does not appear to have been the direct inspiration, but the Queen of Pop has definitely crafted a Holly look or two in her new teaser for the album, thought to be out in early summer:

Beyond the look, will Madonna's Madame X reference Lana's? As ExtraTV reports, she says in the trailer:

Madame X is a secret agent traveling around the world, changing identities, fighting for freedom, bringing light to dark places. Madame X is a dancer, a professor, a head of state, a housekeeper, an equestrian, a prisoner, a student, a mother, a child, a teacher, a nun, a singer, a saint, a whore, and a spy in the house of love. I'm Madame X.

It could be that Madonna's Madame X makes better use of her time while in "X"-ile, so hers could be a feminist take on the hoary tale of sin and redemption.

Perhaps the 2019 Madame X owes something to the 1966 Madame X after all, and if it inspires Madonna's fans to check out Lana Turner's last decent hurrah, all the better.

Lana had MGM watching her back until The Prodigal and produced amazing WWII depictions of the home front shop girl. Said & done, it’s Cora in Postman that’s the best of the oeuvre, Lana’s distraught and clawing but still an angel in head-to-toe spotless white.

Oh, I wasn’t saying “Madame X” is her best movie, just “the mother of all” as a play on the film’s maternal theme. It’s a good film, but “The Postman Always Rings Twice,” “The Bad and the Beautiful” and “Imitation of Life” leave it in the dust.

Wonderful review. I saw Madame X, the Lana version, on TCM this afternoon. I like it more than ever and see more nuances. This is a great Hollywood product. Why should I be ashamed to enjoy it?

Interestingly, Ricardo Montalban is a rich playboy but not a so called Latin lover. I still get upset when Holly leaves Christian. She could have married him under a new identity.

Beautiful colors, sets, atmosphere. John Forsythe’s Clay is really unfeeling in his neglect of his wife. Who can blame her for her infidelity? Plus, Phil really died accidentally.

Could this be re-made with a happy ending?

Thank you for appreciating this film, its stars and Ross Hunter.